Solar Dev Log 2:

Space is big.

I think at this point most of us are aware how big space is.1 But… space is really big. Even a small bit of space, that’s quite big. You might be thinking sure, but what about a really small bit of space, what about the smallest bit of space you could feasibly model in a hard sci fi game about planets in a solar system, isn’t that manageable?

Yeah actually, the distance between planets and moons is tiny, but it’s tiny comparatively, because everything else is so damn big.

So, in Solar, the massively multiplayer hard sci fi real time space opera set inside of a single solar system that I’m designing, I needed to get a rough idea of how big space actually was. The base unit of measurement in a game like this is not actually anything to do with distances, it’s all to do with time. The thing that really matters is about ships making round trips between stations, going somewhere, interacting, and coming back.

Because of the difficulty of secure communications, especially over longer distances, players flying places to do things in person (or at least over local comms) is a really core part of the gameplay, and will vary up the otherwise potentially quite static populations of local stations.

So, distance is really a question of time. How long should it take a ship to go from one station to another, and have a chance for meaningful decisions about navigation or encounters along the way?

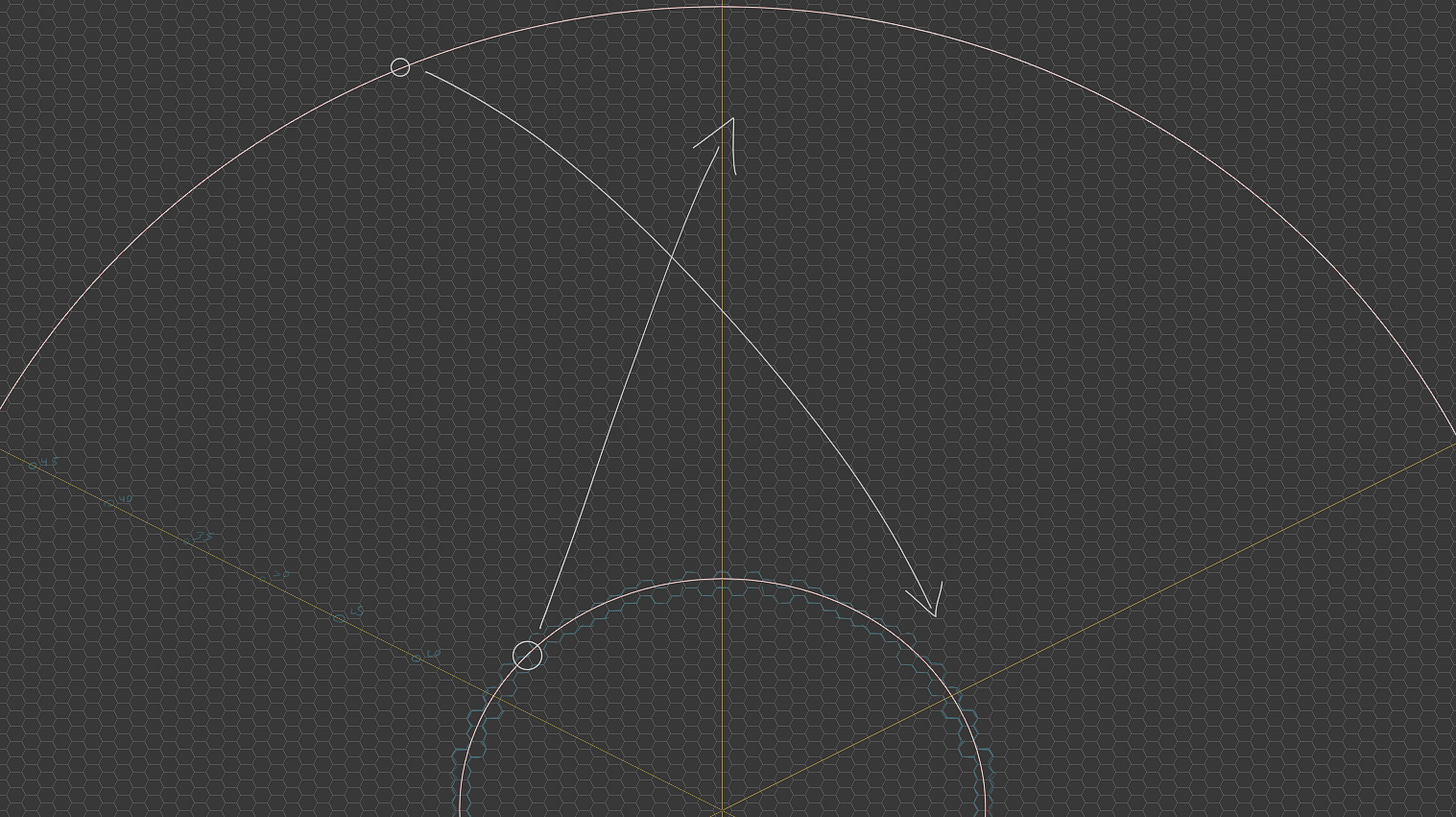

I figured that I wanted my shortest voyages, from one station to another, to take about a week. That’d be three days spinning up, a day of floating, and three days of spinning down. If you leave in the direction that your original station is travelling, you get a free little acceleration boost, and start off at v1, so three days of acceleration gets you up to v4. These are all abstract units, basically just how much you can accelerate in a day, we’ll get to the specifics soon. Then you float at v4 for a day, and decellerate down back to v1 again to smoothly come in to dock with the station you’re heading towards. In total, that’s 2+3+4+4+3+2+1 hexes travelled, or 19, which is now our rule of thumb for a typical gap between stations.

Every extra day we add to the journey increases our maximum range by quite a bit though, because you can add that day in at your highest speed, putting at least 4 bonus hexes in per day to your initial week-long journey. If you have the fuel for it, you can even accelerate up faster than this, and really zip through the system in the middle of a journey. A sixteen day journey like that could cover about seventy hexes; if my napkin maths is about right, peaking out at about nine hexes a day covered in the middle of it.

So… how do you take a map of a fictional solar system, assume that stations are going to be orbiting planets or hanging in asteroid belts, and put them all about 20 hexes from their nearest neighbour. Well… you immediately start plotting them out, and run into another big fundamental problem of space:

Everything is fucking moving.2

Stars are moving, asteroids are moving, planets are absolutely hurtling through space, and the problem is that so much of it is so continuous, so impossibly granular, that abstracting that continuity it in any meaningful way is downright infeasible. I needed to be able to set up some rules that would be easy to implement as a gamerunner, easy for players to understand and plan around, and hint at the real physics of the underlying game, in a way that created meaningful decision points for the players.

So, planets have to move in the game. They’re really the only objects big enough for us to precisely care about on a map//gameplay level, asteroids are small enough that we just track them as fields of space to be careful in, and moons are just satellites attached to their planets.3

But, I decided that planets move at a consistent speed. Every day, every planet ticks along its orbit by one hex. This isn’t particularly realistic. It means that orbital periods are directly proportional to the radius of the orbit, rather than the square of the period relating to the cube of the radius, but… it means that the game works. Our outer orbits, the farthest planets in the system, move much faster than they really should. In the real world, the longest solar orbital periods are on the order of centuries, in this game, none are more than a couple of years. Given that I plan to run the game for six months, this should make the map meaningfully dynamic; stations at war might drift close and then far away from one another as the battles rage on, optimal routes between them represent not a line, but an arcing X crossing at a single point in space, and what was once an efficient trade route might become untenable as it passes through pirate territory for a few weeks.

We get a lot of value, and emergent behaviour, from this relatively simple “planets move one hex per day” rule. Even at this scale, with orbits shown here at 15 hexes and about 50 hexes, the paths they trace are very distinct, and I’m hoping that as they come into and out of phase with one another players naturally intuit or calculate the impact on their strategies.

The downside of this game only lasting for about six months though is that we don’t get to see the full spectrum of interactions. If this game ran much faster than realtime, or you know, lasted for a few real world years simulating out this system, we’d see a much broader range of orbital phase combinations. Especially when thinking about three or four body combos, which matter a lot for things like sophisticated trade routes, there are a lot of possible states that we just won’t get to see here, and some part of me is a little disappointed about that.

Still, it’s probably a bad idea to try and pitch this as an infinite open game just for the sake of experiencing some interesting quirks of navigation several years down the line. I’m happy enough with what we have for our map here.

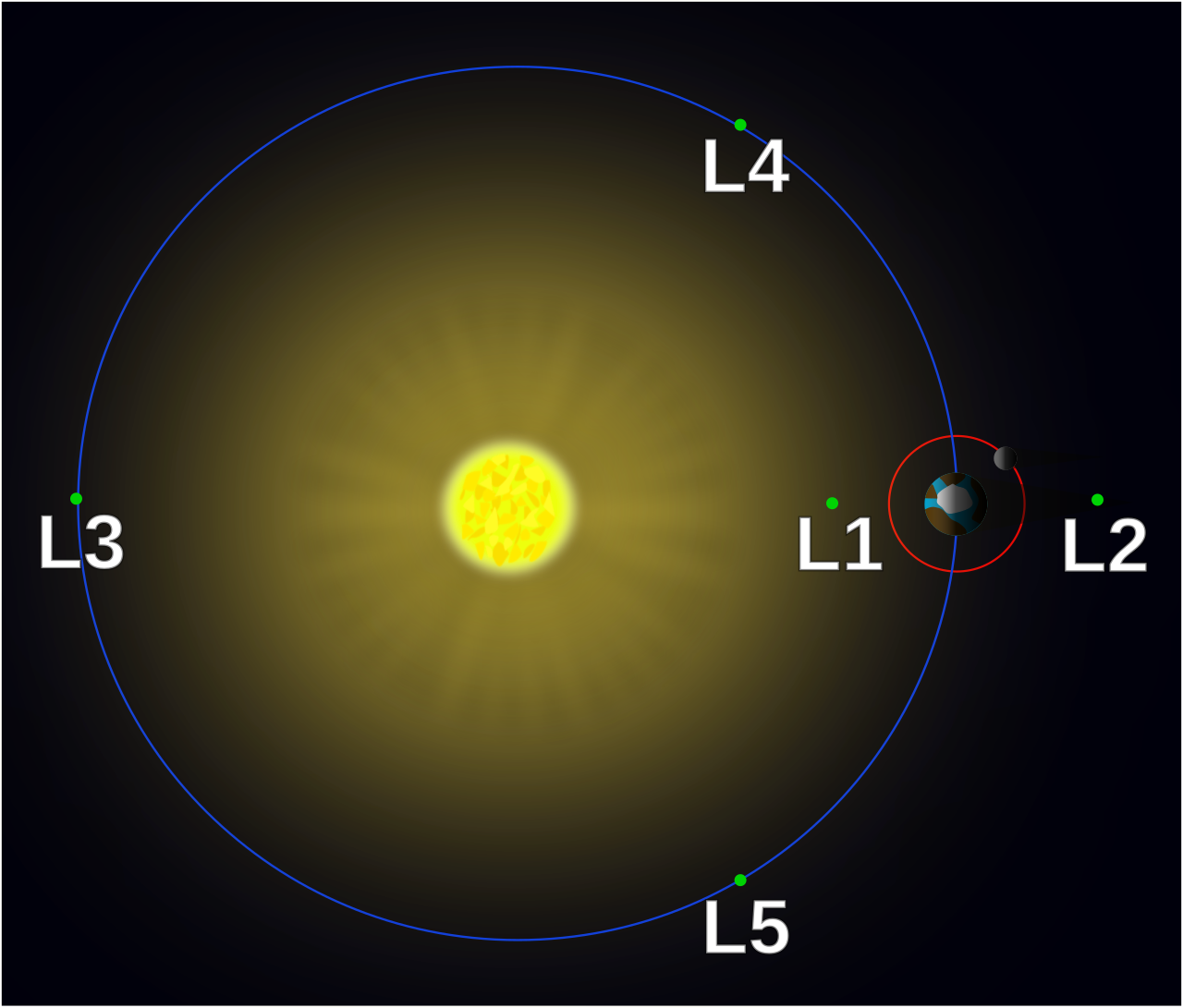

When I said that I was going to populate the system with stations and objects, I want to try and get more value out of each of these orbital paths than just the single planet that follows them, and the gameplay generating space station that occupies that planet’s hex. Thankfully, there’s a wonderful real world phenomenom that we can use for free here: Lagrange points.

When two bodies like this [planet, binary stars] are orbiting, they create a number of stable and unstable points of balanced gravity, called Lagrange points. Small objects4 can gather at these points and orbit pretty stably, only needing occasional corrections to keep them there. In fact, at L4 and L5, impulses don’t even knock it from that point, they just cause it to slowly orbit the point itself on a little kidney bean path. In the real world, this leads to debris and dust clustering at those points, which is an interesting combination of the physics given the millions of kilometres involved almost perpendicularly from the two relevant bodies.

So, some of these points are more usable than others. The distances away from our orbiting planet on L1 and L2 are defined by the ratio between masses, and for an Earth-like planet and a Sun-like star mass, that comes out at about 0.01 AU. On this scale, that means that L1 and L2 are actually our go-to’s for near planet station placement, but don’t show up on the map, they’re sub-hex level.

I should actually define the scope of the hexes. Knowing that movement speed was tied to them, and wanting to get planets on average about 20 hexes apart, I figured our earth like orbit should be at about 15 hexes. That was wide enough that the orbit reads like a circle, that the journey sunwards or outwards means a fair commitment in time and resources, and, it meant that our hex length was a pretty neat 10 million kilometres from centre to centre, to get to Earth’s average orbit of about 150 million kilometres. In actual play, all ship-scale measurements are going to be done in hexes just to avoid ambiguity, but the orbits will be smooth and Mkm based just to avoid perfectly hexagonal orbits. This means that, mechanically, planets shift closer to and further from the stars, but that’s fine because the orbits are elliptical anyway, and it gets averaged out across the orbit.

Back to our Lagrange points, L3, L4, and L5 are 180 degrees, 60 degrees, and 300 degrees off phase in the orbit from the smaller planet, which means that on the grid all of those are guaranteed to be in exact hexes rotated around the origin. This makes them really easy to integrate into the game, and also means that I don’t need to put them on the public map.

It can be a known fact that, for example, Maura L4 sits sixty degrees ahead of Maura Low Orbital in the orbital path, and navigators can calculate it’s location pretty easily (just rotating one hex face around from the origin), but that fact could also be hidden from another faction or a group of players, or changed during the course of play if the station were knocked from its orbit. That means that starting station locations can be partially known information, and also, information very easily betrayed, if people want to get into the dangerous game of treachery and information vending quite quickly.

The stability of these lagrange points also allows for educated guesses at things. They’re valuable places to explore in the early game while people are scouting and gathering information, easy places to park long term projects if anything needs to be constructed out in the void, and handy reference points for navigation and motion, always related to objects too big to ever feasibly hide.

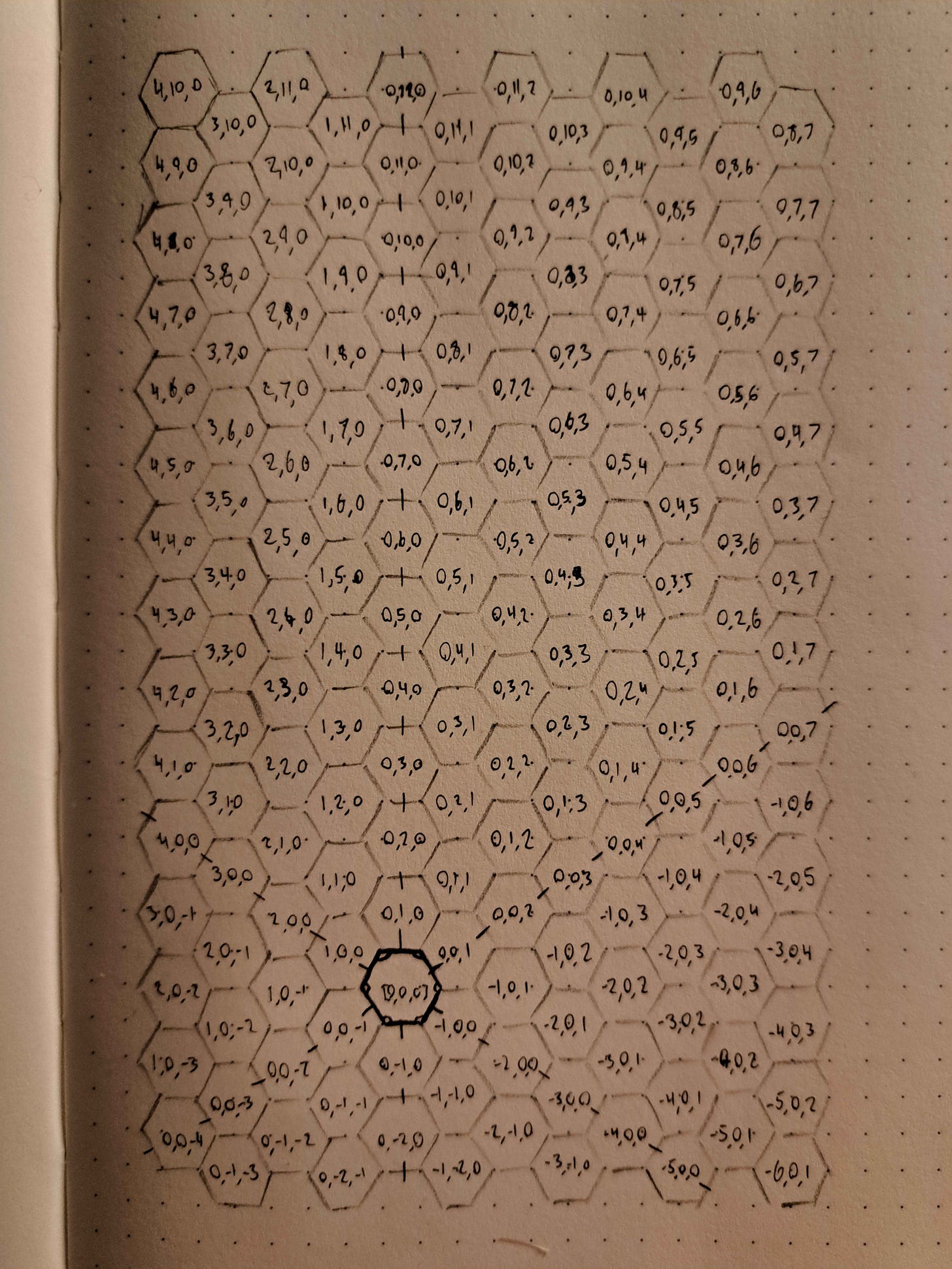

At some point though, we will need to reference a hex that isn’t a planetary location, or one of the handy L3, L4 and L5 points related to it. For that, we need a hex reference system, some way of referring, uniquely, to any hex in the system.

I want this coordinate system to be pretty easily typed. Back in O/U, it was regularly necessary to refer to specific block numbers ([30.06] for example) and I imagine that’ll be similarly useful here. I want it to be numeric, rather than alphanumeric, just because converting hexadecimal can be a challenge to get used to, and would be a barrier to entry. I want it to encode two really important pieces of information as well, I want it to encode distance from the centre of the system, and I want it to encode something about the area of space that the hex is in.

So, cartesian coordinates unfortunately ended up ruled out, they do work as pretty quick reference points once you start dividing them by 300 and scanning across the map, but they don’t really encode anything about our solar centre. There are some beautiful posts about other hex systems, and I spent a long time considering using half-hexes or cube coordinates, but they failed to encode the right kinds of information that I wanted, and had some issues with interpretability. What I ended up with was of course, as best I can tell, a new type of hex coordinate system.

Introducing: Triaxial shortest path hexes!

I might need a better name for these.

The basic premise is that every hex is referred to with a three part signed coordinate, [x.y.z]. This coordinate describes the exact shortest path that must be taken to get from [0.0.0] to the relevant hex, functioning as a vector from the system centre out to the point. It has an additional readability benefit, in columns of hexes rather than rows at least, where positive numbers indicate upwards movement, and negative numbers downwards, as well as being read from left to right meaning that in the positive case, coordinates should be relatively intuitable.

The x axis refers to the line travelling up and to the left from the origin, and its negative travels down and to the right. The y axis is purely vertical, and the z axis is the mirror of the x.

Because this describes the shortest route from the origin to a hex, and any two steps on different non-adjacent axes result in a single step in the intermediate axis, or else a return to your original position, there is always at least one 0 stored in the coordinate, indicating an axis that is not travelled upon. The hex then cannot be in a sector bordering that axis. From the other two, checking the sign on even one axis will unambiguously return the “correct” sector, meaning that with very little practice at all, it’s possible to quite quickly learn to spot the sector of a given coordinate. Finally, any coordinate with two 0s is along one of the axial lines, all of which will be marked clearly on the system map for quick reference, and [0.0.0] is intuitively our solar centre, the point about which all other objects orbit.

The other benefit is that shortest path then naturally encodes the radius as well from the origin, the sum of the absolute digits in the coordinate is always your radius, and that then serves as a really useful benchmark for placing yourself relative to orbital paths. If planet A orbits at 80 hexes from the stars, planet B orbits 105 hexes out, and planet C orbits at 112 hexes out, then by simply checking the signs on the coordinate to get your sector, and adding the digits to get your radial distance, you can immediately narrow your location down to a band of space somewhere out between a few orbits.

The coordinates also produce beautiful, easily read straight cardinal5 lines. Any cardinal line running perpendicular to the origin trades one digit for another, [0.3.4] to [0.4.3] to [0.5.2] and so on, as it maintains the absolute distance from the centre. Any other line, running towards or away from the origin, simply increments one or the other of its digits up or down by one for each step it takes [0.3.4] to [0.3.5] to [0.3.6], as its distance changes step by step.

This is because, secretly, within each sector, this three part coordinate is simply a 2d coordinate referring to a a pair of infinite equilateral triangles, touching at [0.0.0]. When moving within a sector, the difference between your current location and your previous day’s location can be added on to your current location to get your velocity. Going from [1.1.0] to [2.2.0] leaves you travelling, very predictably, to [3.3.0] tomorrow if you decide to simply drift and allow yourself to float in that direction. Even at odd and askew angles, this holds true, and in fact takes advantage of another hidden layer of redundancy within the system.

Though every hex is referred to, on the map, by its shortest possible route of access, it can actually be accessed from an infinite number of different paths, and so for every hex on the map, there exists an infinite family of coordinates that precisely describe it. By restricting ourselves to shortest path, we turn this into a one-to-one mapping rather than a many-to-one, but there is no reason we have to be strict about that during the game itself. A player wanting to run a cryptic scavenger hunt could, for example, hide three fragments of a coordinate listing [3.-.-], [-.4.-], and [-.-.5] respectively, which would describe hex [0.7.2]6 in a relatively oblique way, requiring all three parts to find the correct final hex.

As a result of this, the pattern of “just apply yesterday’s difference to get today’s velocity” actually does hold true even when going across sector boundaries, it simply returns illegal coordinates that don’t appear on the map, but do accurately describe a single specific hex.

So, we have a system that is fairly interpretable (radius and direction), one that encodes specific information into its coordinates, one that has a little redundancy baked in as safeguarding, one that allows for exploiting that redundancy to make information a little harder to access, and one that somehow I haven’t come across before while doing the research for this post.

I personally quite enjoy that any conceivable (integer) coordinate does accurately describe a specific hex, I think I also enjoy that every hex has a specific coordinate that describes the most direct path to it from the stars, but I appreciate that those are somewhat definitely goals in an uneasy mathematical tension, that people might disagree with at some point or another.

Still, with our coordinate system done, I now can put it behind me, and focus my efforts now on v0.5, the update that’s going to revamp factions with new lore and bylaws, and add more guidance on projects and operations.

Thanks so much for reading, I really hope you’re enjoying the continued development. If you’re wanting to engage a little more whith this game while it’s still in development, to remember to check out the discord at the link below, and give the overall rules document a read at some point. Every voice in the community is a welcome addition, and more eyes on the document now (while it’s in v0.5) will help improve it as much as possible before we move towards game launch.

https://discord.com/invite/cuf5gbJ8bY

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1A0RwURbB88LthspkOzqtdw0Dh28YyA4vGhe0wq-kOh8/edit?tab=t.0#heading=h.msjb2ycd3pxp

“You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to space.” - Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy

I don’t have a good Douglas Adams video to reference about this one, so instead think about Tom Scott’s “So You’ve Learned To Teleport” short, it’s good for getting a sense of just how damn much everything is moving all the time, relative to everything else.

There was an early iteration of this game where moons orbited planets a hex away, while planets still orbited the stars at varying distances [oh yeah, it’s a binary star system], but once I started running the maths on it, it led to some weird gameplay interactions, and because of the distance involved, wasn’t really a good physics interpretation, so it got nixed. Maybe in Solar 2.

Anything small enough to exert negligible gravity on the two bodies, so like, a starship, or a space station of millions of people, or… some rocks.

So, technically a cardinal line would just refer to North, South, East or West, but in the absence of a commonly used term to refer to the six lines drawn from one hex to the centres of each adjacent hex, I’m going to use cardinal for this, and I might get evil with it and use ordinal at some point to refer to the cornerwise lines that link [0.0.0] to hexes like [1.1.0] and its ilk.

Remembering that [1.0.1] is equivalent to [0.1.0] helps a lot with calculating what is “wrong” with the depicted hex, and cancelling down until you get a 0 in the coordinate.