Solar Dev Log 1:

The Economics of Over/Under

I need to start this off with a confession, made up of a dozen or two buzzwords that I hope will convey some meaning. I’m designing a massively-multiplayer play-by-post live text roleplaying game.

This is a huge undertaking, and I’m doing my best to distill a decade of games design experience into a few thousand words that will capture all the complexities of a hard sci fi solar system space opera for about six months of play, distributed across a hundred or so players. I am, of course, thinking a lot about fantasy economics these days.

Real world economics are endlessly fascinating, but work very differently to a fictional system. At some point, for the sake of simulation and abstraction, the fictional system needs to stop keeping track of where the money goes. And at some point, it needs to start again. In the real world, things have a habit of existing even when it would be really tedious to keep track of them, which is why we keep finding lost artworks in boltholes and basements. It’s endlessly frustrating, and has spawned the sister fields of accounting and archiving, desperate attempts to record the quantitative and the qualitative truths of the world around us, and the things that we might one day realise we need.

I sadly cannot design a perfect accountant, nor can I simulate a few billion economic agents, even with the help of some very smart programmers and discord bots. So I’m going to have to make some tough choices about where money stops existing, and where it starts again, if I’m to have any hope of giving the players enough economics to sink their teeth into.

Design Goals of Solar Economics

Currently under the working title of Solar (though I’m tempted to just go by Corvettes, a good “Cataphracts” alternative) I have a number of design objectives to hit with the economics of this system. Dotted around the map of the solar system will be a dozen or so space stations, each producing different balances of resources. These range from a few different precious metals, to necessities like water, down to medical supplies like containers of plasma and blood for transfusions, all of which are needed in varying degrees to conduct the great battles of a burgeoning fusion drive era of space travel.

These upcoming six months of dense conflict have been kicked off by the development of fusion drive tech, taking transport times from one station to another from a matter of months to a matter of days. The system just crunched and got a whole lot smaller, and factions previously kept at bay by the difficult logistics of waging long distance wars are now empowered to seize what they want, and deal with the consequences. Warfare is the end point though, a destructive process where well equipped ships burn fuel away in a dance of acceleration and particle cannon fire, send off torpedoes to intercept reinforcements from nearby stations, and tear holes in the infrastructure of the system that may not have time to heal before the next violent outbreak. Before the war, as in any game derived from Cataphracts, is a long period of logistics, reconnaissance, and positioning. The operations level.

Here, trade is essential. A station with good command of its projects and ship bays will produce more vessels for the war, will supply them ably with full fuel tanks and missile tubes, will have materials spare for fast repairs if they’re damaged, and can pay spacers for handy tips about when captains depart for war from enemy stations. No faction starts play self sufficient though, the solar system is too vast, and until now, too disconnected for true self-sufficiency. Instead, they will be forced to trade, to steal, to engage with the systems of indirect conflict and manipulation; to play the game.

The solar system now runs on fusion drives, sure, but people run on credits.

Over/Under, and how much is a kilocredit worth anyway?

I’m no stranger to a fictional economy. I’ve put my hours into Runescape and WoW, I’ve studied papers on Eve Online while writing business ethics essays, I’ve spent the last few years thinking far more than I ever wanted to about an fictional imperialist empire’s tax income on a territory called the Barrens. I had to try and weigh up building a trade port in Murderdale, while a general committed mass murder to take a mithril mine from a group of orcs living as foreigners just a region over. I do this with a few thousand people multiple times a year for fun.

But I’d be lying if I said I was thinking about any of them as I wrote the word “kilocredits” into my lore document. That word, that has been entered into my mind by Mothership. It’s not that I like the ttrpg, or have even played it (it doesn’t really grab me as my kind of game), but the game Over/Under that ran through Mothership Month took about 500 hours of my waking life from start to finish, and will likely have an impact through the next few decades of it echoing in my social game design.

I could talk extensively about the social games of Over/Under, the romance and politics, the optics and soft power, deception and infiltration, trust and espionage, I could talk about art and community and culture, about the way that languages developed and grew in that space, about fear, about paranoia, all of it. But most relevant to me right now is simple, compared to the complexities of human experience.

I need to look at the credits.

Over/Under was a trio of economic games stacked atop one another. At the highest level, a wargame. A map of the station, forty klicks by twenty decks, distributed into territory owned by six factions. At this level, squads are ordered around by Faction Bosses, blocks are taxed for income, factories are worked and goods are shipped out on docks. A fairly mechanically simple wargame plays out.

Beneath that, factions are made up of players. Each faction tracks its membership, it encourages player character denizens to join up, to be paid a wage that’ll stave off their oxygen tax, to be part of an organisation and help it win the game. These signups, on their own, matter immensely. For every denizen you can have, you can tax another block of territory to gain income. For every ten, you can raise a new squad, or assign them to work a factory, or set twenty five of them on a dock. These options reward active recruiting, and give the larger factions incredible muscles to play with, especially when they leverage their unique advantages as force multipliers.

At the most immediate level of play though, the denizens have the power to transfer money between one another, and to this end, players run bars, gamble on “horse” races, host fight nights and dating shows and proms, write compelling travelogue prose in the guise of Anthony Bourdain, or simply apologise, profusely and professionally, at all hours of the day, for money. This layer thrives on player defined objectives. Most transfers are not motivated by any desire to avoid Choking out by failing to pay the upkeep, and very few are motivated by the Top Ten board, a tracker of the most affluent denizens of the dream. Most people engage at this level because it is fun. Transferring someone a few kilocredits for a jacket makes that jacket feel real, it makes it feel valuable. Because a game action happened, and one of some magnitude, there is a record of the jacket’s existence encoded into the transfer history of the station, but a transfer always takes two players, and is always lossless. So this economy is actually a service one, you pay someone three kilocredits in return for them providing you the experience of buying a jacket, they might roleplay out a fitting, talk to you about materials and cut and style, give you narrative details to draw on in the future that bring the object to life. I’ve spoken a little to people about sex work in FFXIV, and it’s really interesting the way that resources flow in a similar fashion for basically everything in O/U. Not to say that everything anybody did in that game was sex work, but a lot of it was pure service for money, and that’s a really interesting basis for a player economy.

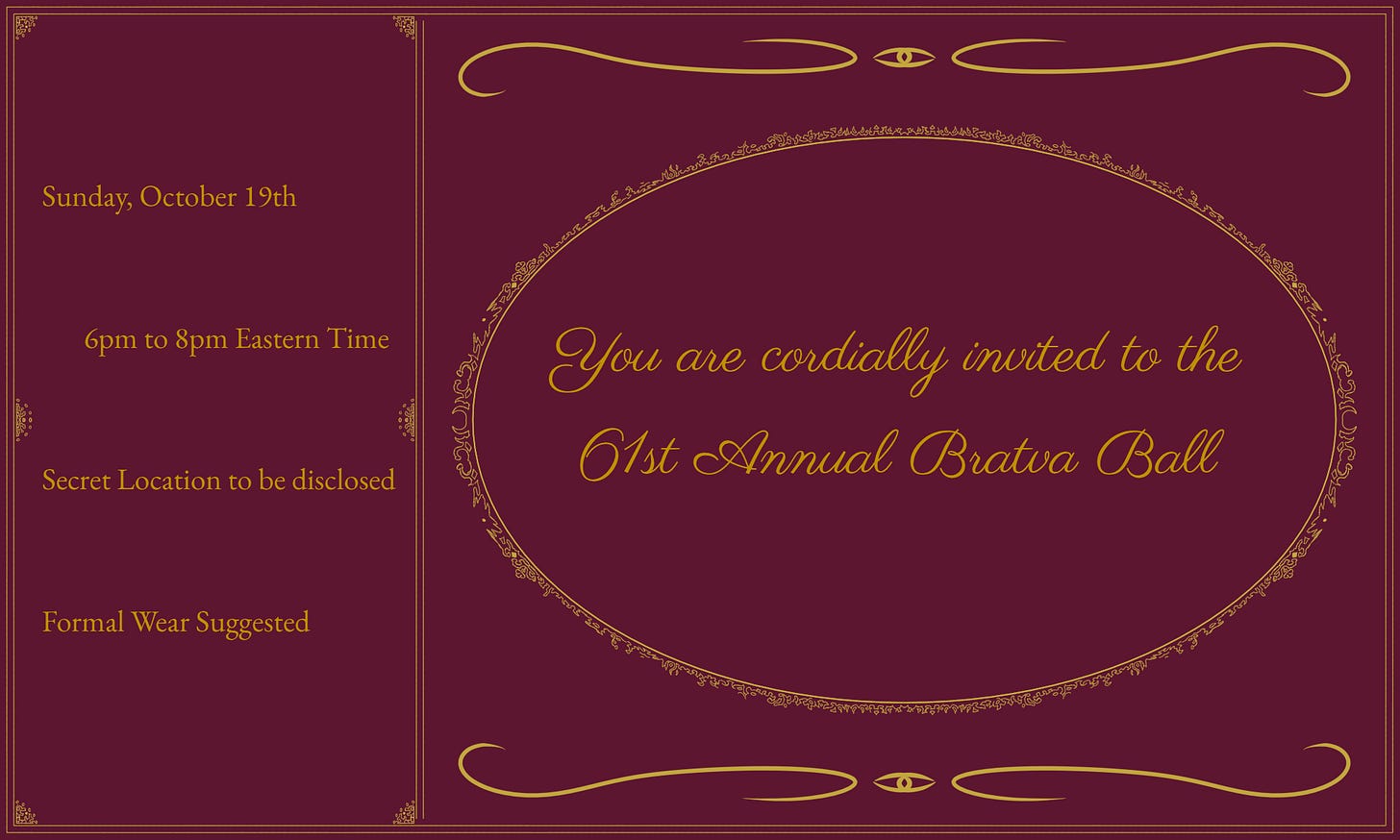

The losslessness is critical here though, transfers do not take money in or out of the system. At this layer, the only output is not survival, we already accounted for that, but opulence: players choosing to spend far more than necessary on their Upkeep to make a play for the Top Ten. There were splashy plays there, cardinals paying hundreds of kilos a day, a Vor of the Golyanovo Bratva spending 2mcr on “horse” breeding, publicly visible to everyone on the station each time the Top Ten was updated. They were status plays, and a chance to spend credits on acclaim, and by the end of the game, the ten players who had featured most prominently, most lavishly, each won their accolades.

The Spouts and Drains of the Station - Economic Sewage Systems

All of that describes the way that money moved through the system, but we can take a step a little further out from that. We can ask concretely what were our inputs, what were our outputs to that system? When did the money start and stop existing, setting aside all of the movement it did internally.

Taxes are the easiest to calculate. On average, a block had 7000 npcs living in it, so when a single denizen was assigned to block taxation, they generated 7kcr/day in income. There were 800 blocks in the dream, but at any point in the game I’m fairly certain that fewer than 200 were ever taxed at a time. Still, this gave us a floor on faction economic activity. If it had enough blocks under its control, then every denizen in a faction generated 7kcr/day in revenue.

Salaries varied across the course of the game, but by the end, most hovered around 1kcr. I’m going to keep the numbers at 1kcr/denizen for simplicity, but in truth, it changes very little. Every single denizen in the dream, roughly a thousand by the end of the game, being paid a kilocredit a day meant that 1mcr was going into the denizen layer of the economy every 24hrs. Once that money entered that third layer of circulation, it seldom found its way out. Denizens simply didn’t have the ability to contribute meaningful amounts of their earnings up to a faction level tier, at best donating a few kilos here and there, maybe a hundred or so over the course of the game. Nothing, compared to the tax income they could generate over a month, and not scalable. For denizens, each day the economy played out like a short zero sum game. Until Zhenya, the discord bot, processed upkeep, there was nothing to truly spend credits on, only transfer them from one player to another. This was a facsimile of trade, an allusion to a realistic economy, but one where every business that was ever set up had an operating cost of 0. Board game shops, bars, kink leather boudoirs, betting rings, artists and painters and everything in between, all of them did what they did with no cost at all, so everything they were transferred was pure profit. It created a fascinating, and at times painfully shallow, economy to follow.

The real money though wasn’t in tax upkeep. Had the whole Dream been taxed every day, it would have generated around 5.6mcr/day. A single container of cybernetics, produced at a rate of one per day per factory, sold at a dock for almost that full amount, and took ten players to produce, not eight hundred. Across the station there were three such factories. Better still than cybernetics for scaling were drugs, worth millions of credits per container, produced just as frequently, but at one container a day per fifty solarian faithful. According to the High Gardener, the church generated 114mcr over the course of the game from this drug trade alone.

The economy of O/U was plagued by inflation, the spectre that haunts almost every virtual economy, as salaries skyrocketed from the 100cr/day of the early game, to the exorbitant 1500+ that almost every faction adopted by the end of it. Drinks that sold for a credit or two at game start went for hundreds by the end, the concept of moving blocks went from a far off pipe dream to be saved up for over weeks, to something players had done on a whim, or to reinforce narrative beats, underscore romances or demonstrate loyalty. I want to be clear, this inflation isn’t a failure of design, in fact from some of the discussions Sam had in the post O/U channels, it seems to have been a fairly predicted outcome over the course of the game. It’s much much better for a game like this to spiral upwards over its lifespan than downwards, an economy without enough money coming in would have seen a lot more players choke out, and a lot less roleplaying and gameplay happening at basically every turn. Not that that wouldn’t have been thematic as hell for a game based on A Pound of Flesh, but, it probably wouldn’t have been nearly as fun for the celebrants of Mothership Month.

At some point the question in game was raised about whether it would be possible to pay for the o2 tax of every single denizen aboard the station of Prospero’s Dream. That 5.6mcr income from taxes? That’s a tenth of the o2 tax, the calculation for how much it’d cost a day was actually trivially easy to get my hands on once I became a faction boss. But whether the station could generate 56mcr/day every day? That was a much taller ask.

In the end, we got a resounding maybe. Maybe, with every arms factory, every cyber factory, every drug container that the Aarnivalkea could produce getting produced, maybe. It would’ve been a close thing, limited greatly by the export caps of docks, the logistical perfection of getting every container to the docks in the right numbers in the right waves, the denizens to work those factories. Working that out, alongside the Tempest Maths Department, was some of the most fun in-setting economics I’ve ever gotten to do, and I think about it a lot while I’m designing the setup for Solar. In the postgame, we have the numbers, and it was definitely possible. It would’ve taken near full church conversion rates, mass demilitarisation, an eviction of tempest and CHC members to the union and the bratva, the handing over of factories to a centralised authority responsible for making sure they were efficiently shipped. Had the game run for six months, I think we might’ve done it, simply as an exercise in maths. I definitely would have tried.

But in the end, it didn’t matter on anything but a narrative level. No player characters, no active ones certainly, were ever at risk of falling prey to the o2 tax after about the third day. Some people did die to upkeep, but they had always gambled away their last coins, or chosen to let themselves be taken by the cold tick of Zhenya’s script. From a narrative perspective, the quest to unburden the station of the o2 tax was a noble one. But in gameplay? It had simply ceased to be a threat to any denizen that could express a feeling in comms.

After doing a full accounting, looking over the sheets shared by Sam and the other bosses in the postgame channels, I can lay the system bare and look at it exposed. Let’s have a look at the spouts, the things that pour credits *in* to the economy.

- Blocks taxed, up to 5.6mcr/day

- Sixty consumer goods factories, up to 6mcr/day

- Ten arms factories, up to 5mcr/day

- Three cybernetics factories, up to 15mcr/day

- One drug container per fifty faithful, 3mcr/50faithful/day, at full conversion, 60mcr/day, at half, 30mcr/day

- Eight docks, shipping up to eighty containers/day, necessary to liquefy any of these containers into credits

You can see that this is dominated by cybernetics and drugs, fairly fitting for A Pound of Flesh’s Prospero’s Dream, but at five hundred faithful, eighty containers a day could be distributed as 10 drugs, 3 cybernetics, 10 arms, 37 consumer goods, for a total of 53.7mcr income. There was a discussion about opening an additional dock, an old defunct port near the chc end of the station, that would’ve expanded revenue by another millicredit in consumer goods output, but you can see the general picture here. Plus some taxation, it turns out that 56mcr was achievable, if barely.

The outputs are a little more varied, but no more complex. Waging war costs credits, squads are raised for 100kcr each, but take attrition over time, and cannot be healed, only reformed by paying the hundred again. Running intelligence operations, for any but the Canyonheavy Cowboys, cost credits, as did assassinations on denizens or bosses. And every day, every person pays their o2 tax and their lifestyle upkeep, which leaves the player circulation. By the end of the game, more active players were luxuriant than not, the highest tier of lifestyle, costing a kilocredit a day. Every faction could cover that with its salary without issue. A thousand players, paying a thousand a day, is still only a single mcr on the scope of the whole station.

- 1000 luxuriant players’ lifestyles, 1mcr/day

- 1000 players’ o2 tax, 10kcr/day

- Intel operations and assassinations - variable

- Squad recruitment - variable, max 100kcr/day/squad

And that’s it.

In terms of actual concrete costs, unavoidable consequences of life on the dream, operating costs, 1.01mcr/day. And that’s with every citizen at luxuriant. So for a quick worked example, Tempest Company spent around 1mcr, through the whole game, on raising squads, and maybe another 1mcr on intel ops, and had next to no other expenses. The salary of officers amounted to about 2.5mcr over the course of the entire game, thanks to an officer count of about a hundred and a comparatively low pay rate compared to more affluent factions. Near the end of the game, a sale of ten crates of arms for 5mcr covered absolutely all of Tempest’s operating costs for the month of O/U, including fighting two victorious wars. You can see why inflation became an issue.

The economics included vastly more inflows than they did out. Now the intent had been for this vast wealth to get spent on intel ops and assassinations, but actually what it resulted in was absolutely insane overspending. Private denizens with intelligence were demanding obscene prices for their services, auctions for artworks went for hundreds of kilos or millions, not that this is unrealistic, but it’s an odd consequence in a wargame, and not one that I think everyone would have predicted. The Golyanovo Bratva established a Public Works programme, an opportunity for denizens to pitch various ideas for events to run and be paid for those things to happen. But because operating costs were fictionalised, a lot of it felt like kickstarter backer goals that could have been in the book from the start. Paying 2mcr to renovate a theatre meant a lot less when it was done for free on the backend. That 2mcr had just been pocketed somewhere, and was in a private denizen’s account. For a lot of denizens, that scam became the game, find the factions with money generation, and embezzle as much as possible without burning your goodwill.

The Variable Costs - Assassinations, Intelligence, and Opulence

Interestingly, assassinations accounted for remarkably little of the game’s overall spending. Because so many denizens were well liked or interconnected, any assassination came with a heavy social cost, and driving your faction members to quit or leave, or turn traitor and sell your information, was too steep a price in many cases to make assassination a worthwhile tool to use. It was deployed sparingly, and maybe only a dozen people over the course of the game took a bullet from the bratva. Intel Ops, too, were of very limited use.

The Union had its hands bound by democratic process, most intel ops worth running cost more than the maximum discretionary spending available to Union bosses without a vote, and a 24hr referendum before any fact checking mission gave opponents ample time to set up counter intel, or simply change the facts, before they became relevant.

Tempest never had enough funds to spend on intel operations, it had a faction goal of finishing with 25mcr in the reserves; and lacking any economic tools, or much economic benefit to taking a faction HQ or its blocks without the bodies to work them, contract work was thin on the ground for much of the game. The mercenary company floundered for a lot of the month, struggling to find sources of income to exploit. The arms sale was overlooked for a long portion of the game, logistically very difficult, and after a turbulent handover period where most tempest bosses resigned or died, it took time to renegotiate those contracts, so a lot of potential profit was lost, and the company didn’t really have any other means of generating appreciable revenue.

For the Golyanovo II Bratva and the Church though, they had Canyonheavy. Quite early on in the game, the CHC aligned themselves closely with those two factions, the Bratva especially, and the CHC had the ability to run an unlimited number of intel operations without spending a single credit, at the cost of Data Cache Power. Datacache power was generated by the mining of tokens, a minigame that with some practice could generate 1-3kcr/minute/player, so performing millicredit power equivalent operations took a fair amount of input, but was regularly distributed across a broad number of players, and this economy was so efficient compared to anything else that players could do to generate value for their faction that in the end, the Datacache regularly replaced all intel op costs for basically every faction that could access it. That combined with a cumulative experience in writing intel ops that yielded valuable results meant that the CHC bosses were often the best and most efficient port of call when wanting to find something out, even if you did have the funds to discover it yourself.

In the end then, very little money was spent on intel ops each day, remarkably little actually, compared to the inflow scale, and that meant that money circulated and accumulated, inflating the economy ever further as the weeks went by. As the stretchiest piece of game design, the output that could easily have taken millions a day or nothing, a lot of economic stability was depending on intel ops being fairly bounded. But the reward for bypassing them and spending nothing was absolutely huge, for one reason or another, to basically every faction, and that limited their usefulness as a rubber banding tool on economic output. The other variable, the Top Ten board for lifestyle costs, was a little limited by the scope of denizen inequality; and due to stratified payrates being pretty consistently good across the board, any exploitation ended up taking an immense amount of work, meaning that the successes were the hardest working artists on the station, con or otherwise.

Solar Systems and Corvettes

And now we loop back around to Solar, a game that I want to have a dynamic and thriving playerside economy, especially within and between stations of spacers, that’ll reward the most enterprising players with access to their own ships, or the ability to fund and influence station level projects that change the mechanics of the game.

I know my outflow points; crew costs, fuel expenditure, ship repairs, ship destruction, operations, and projects. And I know my inflow points; station credit, fuel, and container generation. That’s it. At this point in development, those are my full set of tools.

I’m going to need to do a lot of maths, probably run a couple of playtests, to get a good idea of average fuel expenditure per ship so I can set a meaningful price. I’m going to need to design and balance projects carefully, set a series of them up at game start to teach my players the precedent established going forwards, let those complete over the course of months and see where we end up. It’s going to take a lot of fine tuning, and I’m probably going to get it a little wrong. That’s okay. I’m happy to err on the side of inflation, to have an economy that grows and eases up over time, let it be the case that the endgame is more about desire than desperation, that’s all fine.

But the stations are not quite as passive as the background denizens of Prospero’s Dream were. They are my voices, agents when I need them to be, people to whom things can happen and provoke responses, and take chunks from the faction budgets and reserves as they deal with crises in their own territory. All of this is intended to force and serve player agency, to put the characters in a position where interesting choices need to be made, and where the fate of the system diverges as a result of the decisions of my players. If you always have enough money, you never spend a thing. If you never have enough money, you never get the chance to. There’s a delicate balance in the middle there, but it’s a broader band than a lot of people think.

As I design the map, I’m setting up the orbits of these planets on broad ellipticals, and running the maths enough that I’m satisfied. I’m not simulating the chaotic three body problems that emerge from those gravitational systems. With the economics, I cannot simply constrain their orbits in the same way, so I resign myself to the fact that if my clockwork orrery is misaligned then the system careens off to the stars. I hope it doesn’t come to pass, and that if it does, it’ll at least be fun to see the lights sail by.

If you’re interested in reading the in development ruleset for Solar, check out the rules doc here currently in v0.4.

If you’re interested in following along with the development, and chatting with me and the community of people interested in playing, check out this discord link to our server, and come say hi!